Foundations of Analysis

Lecture 1: Holes in the rational numbers.

Much of the subject of real analysis is motivated by

physics. Over the years,

scientists have constructed many models of the physical world which predict its

behavior with increasing accuracy. In the classical models, space and time are

represented as a continuum, rather than as a bunch of tiny pixels packed in some

multi-dimensional arrangement. The notion we have of the continuum is very intu-

itive to the human brain. However, constructing the continuum in a way which is

precise, useful and well organized involves a large degree of abstraction. One

needs

to pin down the abstract mathematical properties of the continuum and

investigate

how these relate to each other.

The main point of our task is to construct or at least

characterize the real line.

To do this we start with the set of rational numbers m/n where m and n are

integers

with n ≠ 0. (Of course we identify m/n with (cm)/(cn) for c ≠ 0.

Ordered Sets. Let S be a set. An order on S is a

relation denoted by < with the

following two properties.

(i) If x ∈ S and y ∈ S then

exactly one of the following three statements is true:

x < y, x = y, y < x.

(ii) If x, y, z ∈ S and x < y and y < z then x < z.

Remark. We write x ≤ y to mean "x < y or x = y", etc..

The rationals are ordered are arranged in a straight line by the ordering

p < q  q - p is positive:

q - p is positive:

Note that a positive rational is one which can be written

as m/n where m and n

have the same sign. For a rational number p, either p is positive or p is zero

or - p

is positive.

The reason that the rationals do not satisfy our intuitive

picture of a continuum

is that they are riddled with holes.

Theorem. There is no rational number whose square is 2.

Proof. Suppose that there exists a rational a/b

such that (a/b)2 = 2. Then by

dividing a and b by a power of 2, we can assume that 2 does not divide both a

and

b. Now we have a2 = 2b2, so a2 is even and hence a is even. (To see that the

square

of an odd number is odd, we notice that (2k + 1)2 = 2(2k2 + 2k) + 1.) But then

4|a2 = 2b2, and 2|b2, so b2 is even, so b is even which is a contradiction.

Definition. Let

A = {p : p > 0, p is rational and p2 < 2}.

Let

B = {p : p > 0, p is rational and p2 > 2}.

For example, some elements of A are given by terms in the

decimal expansion of

1, 1.4, 1.41, 1.414, 1.4142, …

Theorem. A contains no largest element and B contains no smallest element.

Proof. We show that for each p ∈

A we can find q ∈ A with q > p. How should

we choose q? We have p2 < 2 and want q = p + α rational with (p + α)2 < 2. But

if α < 1 then

(p + α)2

= p2 + 2pα + α2 < p2 + (2p + 1)α.

α)2

= p2 + 2pα + α2 < p2 + (2p + 1)α.

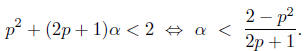

But we can indeed choose α so that the right hand side is less than 2. Indeed,

Similarly for the claim on B.

Remark. More generally it can be shown that if n is

not a square number, then

is irrational. The facts that are needed to prove this general fact are given

is irrational. The facts that are needed to prove this general fact are given

below.

We are going to write down the properties which

characterize the real numbers.

Many texts on the subject actually construct the rational numbers from the

integers

and then construct the real numbers from the rational numbers in a

mathematically

rigorous way. We are not going to do this, only because it takes some time.

However,

the student who is interested should take a look at the appendix to Chapter 1 of

the book.

Supremum and Infimum. Suppose that S is an ordered

set, and E

S.

S.

We say that β ∈ S is an upper bound for E if x ≤ β for

every x ∈ E.

We say that E is bounded above if there exists β ∈ S

which is an upper bound for

E.

We say that β ∈ S is the least upper bound or supremum

of E if β is an upper

bound for E, and if α < β, then α is not an upper bound for E.

Example. S is the rationals. Consider the following subsets E of the rationals:

(1). E = {p : p > 0; p2 < 1}.

2 is an upper bound. 1 is the supremum. 1

E.

E.

(2). E = {p : p > 0; p2 ≤1}.

2 is an upper bound. 1 is the supremum. 1 ∈ E.

(3). E = {p : p > 0}.

E is not bounded above.

(4). E = A = {p : p > 0; p2 < 2}.

2 is an upper bound. There is no supremum for E in S.

Similarly, suppose that S is an ordered set, and E

S.

S.

We say that β ∈ S is a lower bound for E if β ≤ x for

every x ∈ E.

We say that E is bounded below if there exists β ∈ S

which is a lower bound for E.

We say that β ∈ S is the greatest lower bound or

infimum of E if β is a lower bound

for E, and if β < α, then α is not a lower bound for E.

Least Upper Bound Property. An ordered set is said to have

the least upper

bound property if: Whenever E

S is non-empty and

bounded above, then the

S is non-empty and

bounded above, then the

supremum of E exists in S.

We saw that the rationals do not have the least upper bound property.

Appendix: Elementary number theory facts you can

use to show that

is irra-

is irra-

tional if p is prime.

Factorization of integers. In this appendix, Z

denotes the integers and Z+

denotes the positive integers.

If n, d ∈ Z, and n = cd for some c ∈ Z, we say d is a divisor of n or n is a

multiple of d. We write d|n. The integer n > 1 is called prime if its only

positive

divisors are 1 and n. Using the principal of induction, one can show that every

integer n > 1 can be represented as a product of prime factors in only one way,

apart from the order of the factors. This is known as the Fundamental Theorem of

Arithmetic. For our purposes right now, we just want the following:

Theorem 1.8 If a prime p divides ab then p|a or p|b. More generally if a prime p

divides

then it divides at least one of the factors.

then it divides at least one of the factors.

Clearly we only need to show this for a and b positive. For a and b in Z+, we

denote by (a, b) the largest positive integer which divides both a and b.

Theorem 1.6 If a, b ∈ Z+ have (a, b) = 1, then we can find integers x and y with

1 = ax + by:

Proof. By induction. If a = b = 1 then this is trivial because

1 = 1 · 1 + 1 · 0.

We will carry out induction on the maximum of a and b. Assume the statement

has been proven when this maximum is at most n ≥ 1, and now consider the case

when the maximum equals n + 1. Without loss of generality assume a ≤ b. We

only have something to prove in the case (a, b) = 1, and since b > 1 this

implies

that a < b. (Else a = b and (a, b) = b > 1.) Hence 1 ≤ a ≤ b. But the maximum of

a and b - a is less than b. Moreover, (a, b - a) = (a, b) = 1. Hence by

induction,

1 = ax + (b - a)y,

for some integers x and y. But then

1 = a(x - y) + by.

By induction, we have proved the result.

Now we can complete the proof of Theorem 1.8. Indeed, if p|ab but p does not

divide a, then (a, p) = 1, so we can find integers x and y with

1 = ax + py:

But then

b = abx + pby

and p divides the right hand side so p|b.

The value d is called the greatest common divisor of a and b and is denoted by

(a, b). Any other common divisor of a and b must divide it.